This is the view from the second floor over the lobby that stands under the great dome at MIT. I walked by and often stood at this particular spot nearly every day for a few years back in the 80s and 90s, and there was always something interesting to see either inside or out: the skyline across the river, tickets and events information at lunchtime, engineering students in a bridge-building competition, or the regal rhododendron in full bloom along the perimeter of Killian Court outside. After I left the Institute I returned to the Lobby a few times to sell hand painted clothes at the craft fairs. It was lovely to work in such a busy and imposing structure; it made every task seem useful and important and sometimes I would invent reasons just to take that walk down the Infinite Corridor and feel the buzz. I miss it sometimes but on recent visits have found that the nostalgia of the architecture is not enough; it was the people and the work that kept me going, and I would almost prefer to look at the photos than walk down the corridors where, now, nobody knows my name.

Home Windows – a reading spot

It’s been a while since I posted any window photos, though I have taken many. This one is in the house where I grew up, looking much the same now as it did then. We used to climb though the windows on the left and right to sun ourselves on the warm tar roof during cold April days. It was a sign of spring. The vantage point from which the photo was taken was where my mother kept her cedar chest, and I imagine it full of wool blankets and linen and lace wrapped in brown paper – to be honest I am not sure if that’s what was really in the chest or I am just channeling all of those Laura Ingalls Wilder books I read on that landing, my body wedged between the radiator and the window. But I do still have lace and linen wrapped in paper from that house, that much is certain, and I wonder now when I will ever have occasion to use them. They’ve been waiting for their moment for so long.

It’s been a while since I posted any window photos, though I have taken many. This one is in the house where I grew up, looking much the same now as it did then. We used to climb though the windows on the left and right to sun ourselves on the warm tar roof during cold April days. It was a sign of spring. The vantage point from which the photo was taken was where my mother kept her cedar chest, and I imagine it full of wool blankets and linen and lace wrapped in brown paper – to be honest I am not sure if that’s what was really in the chest or I am just channeling all of those Laura Ingalls Wilder books I read on that landing, my body wedged between the radiator and the window. But I do still have lace and linen wrapped in paper from that house, that much is certain, and I wonder now when I will ever have occasion to use them. They’ve been waiting for their moment for so long.

Steve Martin: Pied Piper with a Banjo

I work out to Steve Martin‘s banjo music. I imagine he would be appalled to know that, but then again maybe it’s a marketing idea. I sort of admire people who can go the gym and work out regularly but I am not one of them. The idea of getting in my car and driving somewhere to exercise just seems wrong, not to mention embarrassing for someone who refuses to wear sweatpants anywhere, ever. If it’s too cold to walk outside, looking out the basement window and listening to The Crow gives my mind something wonderful to do while my body is busy being miserable. It’s perfect. Forget Katy Perry, Michael Jackson and the rest of the thumping-base workout music – it all only reminds me of how young I am not. But banjo music brings out the young in everyone. It is inherently happy, endlessly sunny and an invitation to love life. The winter melts to spring, the rural roads stretch before me, and when I am finished I can go and write.

Speaking of which, a while back my daughter and I went to hear Steve Martin himself talk about his life and play a little banjo. At the end of the interview by insipid entertainment reporter Joyce Kulhawik (I am loathe to even give her a link), Mr. Martin took questions. One person whined to him about writer’s block and asked him how he kept himself creative and he was blissfully bemused. In effect, he told her that, having worked so hard to get to this point in his life that he can now pursue his ideas whenever the mood strikes him. No pep talks, no tricks of the trade, just a very candid glimpse of someone who has earned the right to do nothing and thus pursues everything. Think about it – writer, comedian, actor, director, playwright, poet, collector, musician. Even if you did have writer’s block how could you think someone like Steve Martin could provide you with any more wisdom than he already has?

It’s that time again – January, and an election year to boot

How many platitudes, resolutions and predictions can you cram into one January blog post? The mind reels. But times are changing and I can’t stop thinking about it because it all seems so overwhelming good and bad – it’s exhausting to move so constantly from depression to enthusiasm to panic in sub-zero weather. Coffee. Wine. Cupcakes. Stale Christmas cookies. I’ve tried them all. And I just read on the Internet – on Science Daily, no less – that people who write about their emotions regularly are more likely to lose weight. Seriously. So I put down my cupcake and here I am, typing away on my fabulous new computer on which I should be writing anyway because, well, what else am I going to do while the plumber is here fixing my bathroom? Unfortunately the article does not give me a word count to reach before I can return to my cupcake.

But seriously, 2012 is bound to be a doozy one way or the other, right? The Iowa Caucuses alone constitute a shot over the bow. And even though that is indeed a link to the Daily Show’s coverage of the caucuses, pretty much any coverage of it is hilarious. I’m not rushing out the door this year to take in the New Hampshire primary scramble this year, though, oddly tempting as a Newt Gingrich sighting might be. Back in 2008, I spent the day after the caucuses tracking down Hillary Clinton and John McCain.

I watched Bill and Chelsea Clinton, wearing pained expressions as they watched Hillary try to recover from her loss to Obama the night before.

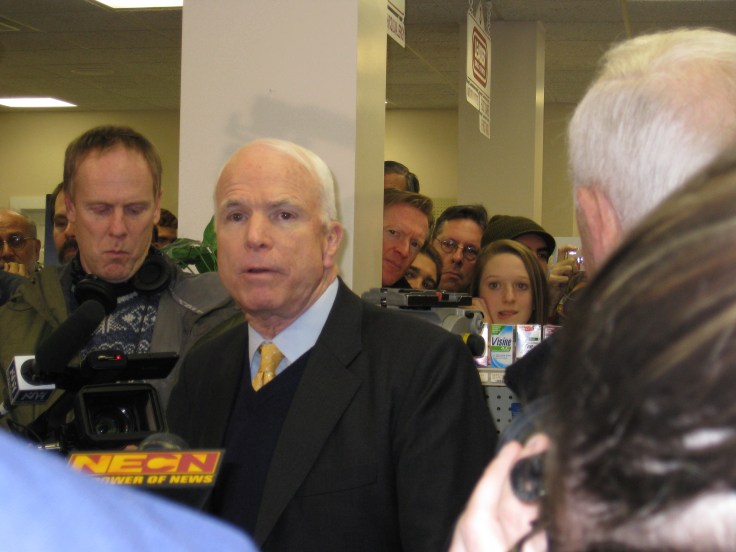

I witnessed McCain’s last retail style appearance at a Hollis, NH, pharmacy in which I was one of a handful of people who saw Warren Rudman endorsing McCain. The tiny store was so jammed with press people and equipment there was no room for actual voters – Cindy wisely stayed on the straight talk express bus. after that, it was all Town Hall style venues. I also spent some quality time observing CNN’s John King at work in the still-empty country pharmacy as he waited for McCain to appear. This was before he was promoted to the role of smart screen guru in the studio – I recall being in awe of his ability to talk on a cell phone, look at a Blackberry and type on his laptop all at once. Even just 4 years ago that kind of multitasking was novel stuff. Still, he took time out to chat about the momentous events in Iowa and was relaxed and personable even as he continued to work and the room slowly filled with people around him. It was probably the best January morning I have ever spent anywhere. Mitt, Rick and Newt could not hope to come close.

It was probably the best January morning I have ever spent anywhere. Mitt, Rick and Newt could not hope to come close.

Predicting the Unpredictable

Last week my youngest told me that if he could go back in time, he would find the terrorist headquarters and blow it up – he actually said he would sacrifice himself – so that 9/11 would never have happened. That’s the lesson he brought to this day. When I told him that we can never quite know what might have prevented that day ten years ago, he found that answer wholly unsatisfactory and I don’t blame him. I didn’t like it either, but I also know that my childhood was laced with an understanding that we weren’t expected to control our futures, only to prepare ourselves to lead the best life we could with the blessings we have. Among the many disillusionments of the 21st century, this responsibility to control everything in life that we are imposing on our children, and its attendant assignment of blame for every mishap, is the biggest one. What was once the ebb and flow of daily life has turned into a lady or the tiger conundrum every single day.

Last week my youngest told me that if he could go back in time, he would find the terrorist headquarters and blow it up – he actually said he would sacrifice himself – so that 9/11 would never have happened. That’s the lesson he brought to this day. When I told him that we can never quite know what might have prevented that day ten years ago, he found that answer wholly unsatisfactory and I don’t blame him. I didn’t like it either, but I also know that my childhood was laced with an understanding that we weren’t expected to control our futures, only to prepare ourselves to lead the best life we could with the blessings we have. Among the many disillusionments of the 21st century, this responsibility to control everything in life that we are imposing on our children, and its attendant assignment of blame for every mishap, is the biggest one. What was once the ebb and flow of daily life has turned into a lady or the tiger conundrum every single day.

Now more than ever, it seems we are trying to predict the future and we are still surprised when we are wrong. With the 24 hour news cycle, smartphones and iPad apps, the media devotes so much time and space to people saying they know what the future holds interspersed with other people trying to say they saw the most recent disaster coming followed by a systematic and relentless assignment of blame. What is wrong with this picture? How do we calculate our success rate in preventing catastrophe? Most of the time the people who saw it coming – if there are any – cannot be found on CNN, Fox or the Huffington Post, that’s for sure.

There was a time when the most we could expect to warn us of disaster was the tornado siren. What we have now that earlier generations did not is a bombardment of information that gives us the illusion that whatever happens, we should see it coming. We spent days preparing and watching hurricane Irene blast up the coast only to have her ravage inland rivers – apparently, no one warned Vermont. All of the tsunami sensors in the Pacific did not dissuade Japan from placing a nuclear power plant on the coast. And all of those big banks got hoodwinked by the ratings agencies and never noticed all of those bad loans they were underwriting. It’s no wonder we scratch our heads and wonder how we missed it because as time goes by our mistakes seem ever more stupid and obvious.

Pick a topic – our health, the economy, or the weather – there are any number of solutions to it that are just a click away. And yet, the flow of disasters almost seem to speed up rather than abating with all of this new knowledge and the ability to communicate it. If we leave the TV and the internet on, we are fed, ever so smoothly, the myth that we can prevent bad things from happening when in some respects the bad things are perpetuated by us sitting in front of the screen. And the more preposterous and untenable the theory, the better – we reward the wing nuts: I watched the movie Network last spring and it could have been a documentary.

The moment of revelation in youth that people do terrible things for reasons we cannot understand is one we never forget, and a certain part of our lives is indeed devoted to trying to avert the personal disasters we have known in the forms of death, illness, poverty and pain. Those moments stand juxtaposed with the more collective events for which we don’t feel any personal culpability but then feel compelled to do something about: My parents had Pearl Harbor as a defining moment (and that came on the heels of the Great Depression), the following generation had the death of President Kennedy (followed by the Viet Nam war and Watergate), and we have this day (followed by two wars and a financial meltdown). What one generation does in response to its challenges defines the generation that follows, and I don’t pretend to know that that means for my children – I’m not getting into the prediction business.

Many years ago my cousin was dying of cancer, and she removed every newspaper, magazine and television from her home so that she could focus on her art and on helping others (she offered free financial advice to retirees). I admired her focus but recall thinking that I would never shut myself off from the world the way that she did, even in those circumstances. Now, as I watch the towers fall yet again, I understand, and yet I watch, hoping to think of something good we can do with my son’s time machine.

City Mouse

It’s still hard for me to grasp that I have lived more than half of my life in the Boston area; I suppose it’s part of my local identity to be from somewhere else. And within this realm I still identify more with the city than the country where I have lived for many years. But so often I feel my heart is in the city. Stopping to take this photograph last weekend gave me a sense of exhilaration and belonging that, hard as I try, I never feel in the woods. In the city my step is surer and quicker, with more bounce and energy. In nature I have to work to see the details, I am so overwhelmed by the vast landscape – but in the city everything pops in the most pleasant way, just as these buildings seem to spring from the earth, each from a separate time, percolating up like the water in the fountain. The city speaks to me, it lets me be alone in a crowd, it asks me to participate on my own terms and dares me to thrive. The very act of driving in is a thrill – coming over the rise on Route 2 in Belmont it’s like Dorothy’s first view of the Emerald City.

Boston in October is an effortless romance – the light and the colors along the sparkling Charles set off the bricks and ivy in ways that are easy to love. And the courtship continues though snowy Christmas with red bows and balsam in the snow on the Public Garden. And then in January the holiday hangover turns eveything gray and bleak and the pall extends all the way out to the county and we hide under our down comforters, look at one another and plead: “please tell me why I live here.” By Saint Patrick’s Day retirement in Arizona seems a viable option. The city sees spring first (though long past that cruel date in March when it is supposed to arrive) and I find myself driving in to see the blooms three weeks ahead of my still snowy garden. When the green mist appears in the branches on Commonwealth Avenue, all winter betrayals are forgotten.

I’ve grown to love the space and quiet of the country and, when the opportunity presents itself, will have a hard time giving up the spring peepers, evening owls and ample parking. I am grateful now, though, for the luxury to tap into my inner city mouse just as I did as a girl back in Iowa, listening to the morning chickadees and blue jays and feeling reassured that my beloved urban landscape is just over the hill.

Dusting Off the Soapbox

I have signed up for another tour of duty advocating for special education in our school district and so am subject to ruminating and ranting about how to do this kind of work without becoming jaded. It’s probably already too late.

The local organizations, committees, boards and councils charged with overseeing or advising school districts are made up of people who have consciously chosen to volunteer and advocate on behalf of students and communities. These are roles people take on outside of their chosen profession; it’s not anyone’s day job (although we could certainly make a cases that it can be a full time job). In larger towns and cities the lines between volunteer organizations and professional and political organizations are distinct, but when it comes to schools (and churches, for that matter) in smaller communities, those lines become blurred.

My point: while the volunteer groups are in it (mostly) for the community and the kids, the same cannot be assumed to be true of educators and staff. Hear me out. At the outset it seems cynical, but education is a business and the currencies are power and turf – for every fabulous, gifted educator there are a dozen for whom it is a job where they do what they need to do, benefits are good, job security is great and the summers are open. Being a teacher or a special education provider doesn’t automatically make someone a better person or make them insightful enough to see what is best for each child; not everyone is equally good at their job. I hasten to add that people who volunteer don’t win the altruism prize automatically, either – they are just as vulnerable to power grabs and turf wars as anyone; for years we had PTA groups who refused to sit in the same room with each other to share fundraising and or even calendar event information.

Parents should recognize that administrators and teachers are under tremendous pressure to perform in a variety of ways, and for some teachers and schools the best way to get your students’ statewide test scores up is to get the children with difficulties assigned to another class or school. Inclusion is a wonderful idea that takes tremendous work to implement successfully; not everyone is up to the task.

I didn’t come to this view quickly or easily myself – someone in my family, a high school teacher and track coach for over 30 years – clued me in ages ago when my kids started school but it took some time for me to grasp his fuller meaning. He advised me that, just as in the business world, educators are (understandably) interested in establishing their place within the educational community and that parents and kids are transients in that world – parents come and go but, especially with unions, colleagues are forever. Sticking together and resisting certain kinds of change among staff peers is key to survival. I remembered this when I learned over the summer that teachers in our district were asking that their non-certified colleagues get the ax, regardless of how successful they were with the kids. I also thought of it during the various search processes where people lobbied to get friends hired or took our staff with them with them to new assignments. People have a right to pursue their professional goals, but sometimes those goals do not match up to those of the students they serve.

Thus, I think parents who advocate for their children with special needs hobble themselves when we assume that everyone at the table is in it only for the kids – we are constantly having to push people to make child-centered decisions because in many cases they really don’t know what that means and making a child-centered decision often means change – and we know that people are naturally resistant to change even when their intentions are good. We have seen again and again that some of the people working with our children do not learn quickly or adapt well to new methodologies. I’m not saying that such educators are not doing their best (though some aren’t); I am just pointing out that they are people who are not inherently more virtuous or altruistic than anyone else, that education is their job, and that parents and volunteer organizations would do well to remember that when they interact with district staff.

When advocating for children who are having difficulties, parents often feel so vulnerable and exposed by the process of asking for help they fail to see clearly what other people bring to bear on the situation. Parents are seldom at their best when their children are the topic of a meeting (duh) and this adds to the power imbalance and increases exponentially the possibility of misunderstanding. Most of the families that come to me at the outset of their interaction with the district tend to exhibit one of two postures: fierce and demanding, or needy and apologetic. The demeanor I strive for – and don’t always achieve – is unrelentingly realistic and collaborative. It requires listening when I don’t feel like it to people I don’t respect, overlooking small slights that are painful for me but that don’t affect my child, arriving with an agenda that has as many bullets praising things that do happen as things that require attention, and advocating for teachers getting what they need so that children get what they need.

Naturally, it is not fair or realistic to assume that everyone is as invested in a child’s success as the parent, or that they are invested in the same way; indeed I have seen several cases where schools offer help and parents decline services. In both schools and families there are so many things competing for attention and resources it’s impossible to give every issue, every child the attention they deserve. The key is to try, and to create and maintain a climate in which that effort is rewarded.

A Temple Grandin Moment

It’s the first day of school and the new ridiculously early schedule and the blazing heat make me feel like I imagine these cows feel – I just want to stand in the shade and barely move and not think at all. I am already nostalgic for summer and the late afternoon moments when, while riding with a car full of kids (autistic and not, for the record) past the farms, all of them would spontaneously start to moo at the grazing cows.